Planning for Student Success

Attending to education and working towards attainment is essential to preparing youth to have the skills they need in order to succeed and be successful both academically and socially.

“I do not think the measure of a civilization is how tall its buildings of concrete are, but rather how well its people have learned to relate to their environment and fellow man.”

-Sun Bear, Chippewa Tribe

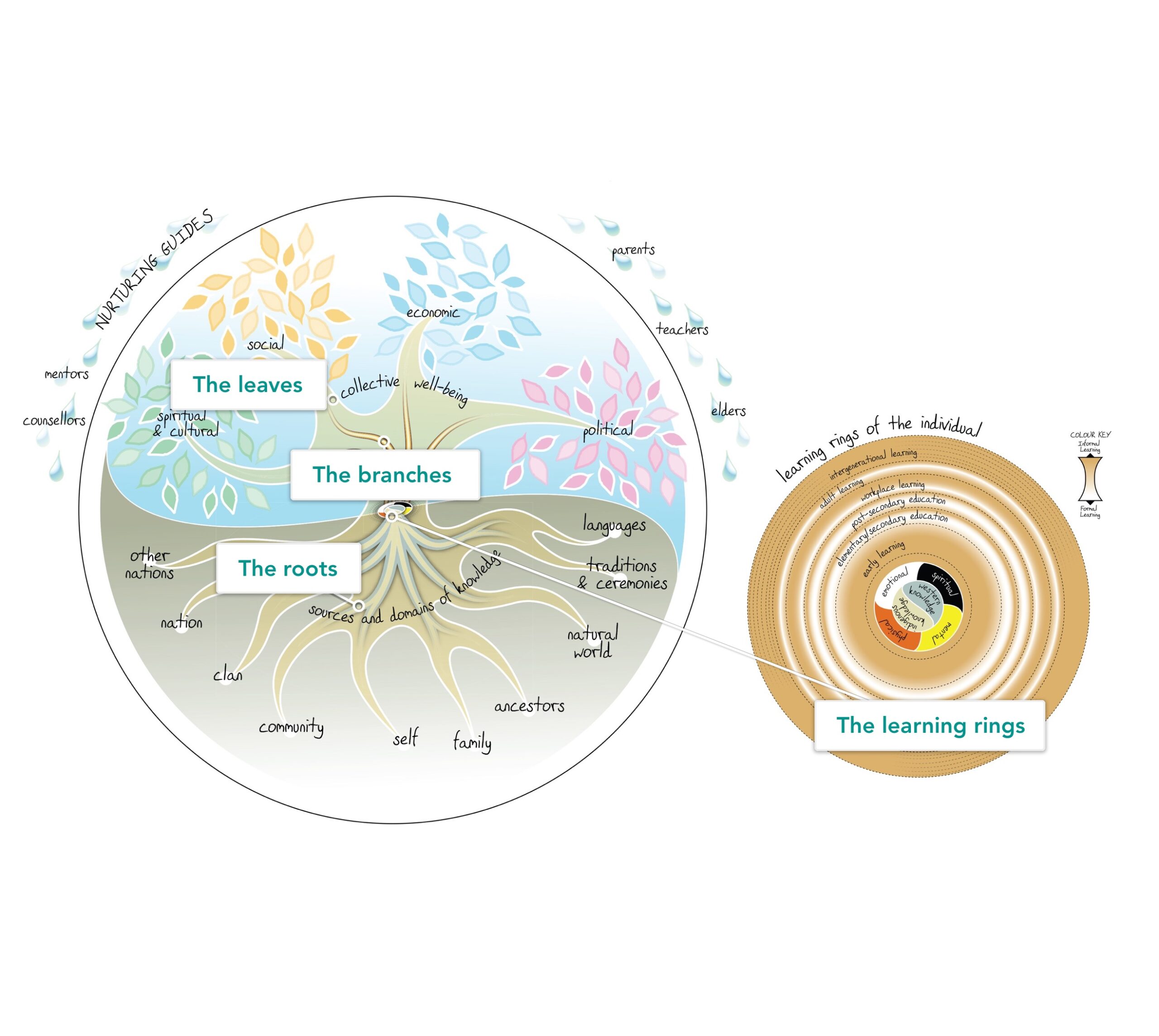

First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model

According to the First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model, the First Nations learner dwells in a world of continual re-formation, where cycles – rather than disconnected events – occur. In this world, everything is interconnectedness. Furthermore, learning is a lifelong process that begins at birth and progresses through childhood and adulthood; knowledge exists across generations.

The First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model can be used to identify what a beneficial platform for learning can look like. It can inform how to move forward in creating lesson plans, individual education plans, or structuring a classroom.

For example, when creating a lesson plan, an educator can reflect by asking:

- Does this lesson incorporate or build upon Traditional Indigenous Knowledge?

- How can I introduce emotional, spiritual, mental and physical learning into this plan?

- Are parents, Elders, mentors, counsellors or community members involved in the learning process?

For more information on the First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model, refer to Plain Talk 9.

View the First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model

The Leaves

Collective well-being. Growing from each branch is a cluster of leaves, corresponding to the four branches of Collective Well-being–cultural, social, political and economic. Vibrant colours indicate aspects of collective well-being that are well developed.

Collective well-being involves a regenerative process of growth, decay and re-growth. The leaves fall and provide nourishment to the roots to support the tree´s foundation. Similarly, the community´s collective well-being rejuvenates the individual´s learning cycle.

The Branches

Individual well-being. The individual experiences personal harmony by learning to balance the spiritual, physical, mental and emotional dimensions of their being. The model depicts these dimensions of personal development as radiating upward from the trunk into the tree´s four branches; each branch corresponds to a dimension of personal development.

The emotional branch, for example, may exemplify the individual´s level of self esteem or the extent to which he or she acknowledges personal gisfts. Likewise, the intellectual branch may depict the level of critical thinking ability and analytical skills, or level of understanding and use of First Nations language.

The Roots

Sources and Domains of Knowledge. Lifelong learning for First Nations people is rooted in their relationships within the natural world and the world of people (self, family, ancestors), and in their experiences of languages, traditions and ceremonies.

These Sources and Domains of Knowledge are represented by the 10 roots that support the tree (learner), and the Indigenous and Western knowledge traditions that flow from them. Just as the tree draws nourishment through its roots, the First Nations individual learns both from and about the sources and domains of knowledge. Any uneven root growth–expresed, for example, as family breakdown, loss of First Nations language–can destabilize the learning tree.

The Learning Rings

A cross-sectional view of the trunk reveals the seven Learning Rings of the Individual. At the trunk´s core, Indigenous and Western knowledge are depicted as two complementary learning approaches.

Surrounding the core are the four dimensions of personal development–spiritual,emotional, physical, and mental–through which learning is experienced.

The tree´s rings portray how learning is a lifelong process. The rings depict the stages of formal learning, from early childhood through post-secondary education and to adult skills training and employment. However, the rings also show the important role of experimential or informal learning. Learning opportunities are available in all stages of life and across all places of learning such as in the home, on the land, or in the school.

Factors in Student Success

In conjunction with using elements from the Lifelong Learning Model, educators and administrators can look to factors for Indigenous student success as researched. Pamela Toulouse, with Laurentian University, compiled a summary of factors that contributed to Indigenous student success.

By looking to these factors, educators and administrators can identify which are being reflected currently in their education system, and how to implement those that are lacking.

These factors include:

- Strong leadership and governance

- High expectations for students

- Focus on academic achievement

- Welcoming education climates

- Respect for local Indigenous cultures

- Quality professional development

- Provision of wide range of programs/services

- Respectful and raised profile of Indigenous students

- Addressing academic and professional knowledge gaps

- Connections with communities

- Involvement of Indigenous child and youth workers

- Hiring of specialized Indigenous resource teachers

- Culturally appropriate curriculum and spaces

- Awareness and promotion of Indigenous protocols

- Sharing of promising practices in education

- Modeling school research and projects

- Valuing traditional knowledge and self-determination

- Youth entrepreneurship programs with businesses

- Accounting and banking mentorships

- Facilitating diverse connections and collaborations

Factors in Creating a Welcoming Environment for First Nations Students

In creating a welcoming environment for First Nations students, it is important to keep in mind these five tenets (Toulouse, 2013):

For non-First Nations schools, it is important to establish networks with Indigenous communities. Toulouse provides a framework for this engagement:

Community Specific Strategies and Practices:

- Gather information on the community through a variety of resources.

Elder Specific Strategies and Practices:

- Learn basic greetings, sayings and terms in the local language when approaching cultural resource people. Understand that language embodies worldview.

- Familiarize self with protocols of approaching cultural resource people and requesting a service. Some may require tobacco as a ‘good way’ to begin.

- Recognize that cultural resource people provide an experience that cannot be replicated by the majority of teachers. Their stories and skills are unique.