Why is it Important to Engage Your Community?

The idea that children are born into and grow up in a social environment is common throughout the world’s diverse cultures. Part of this idea is that children are naturally connected with everyone in their family, community, and town. First Nations, although they differ in customs, traditions, stories and languages, share this concept of connectedness, and extend it by understanding that the role of community members is to assist and nurture the development and growth of children in their communities.

“As First Nations people, we know that when children are born they have inherited all kinds of gifts. It is up to the Elders, to the Aunties and Uncles to observe each child and to identify the nature of the gifts. Does the child have a feel for colour and design? A talent for hunting and tracking? An interest in flowers and plants? Story-telling?

It is the responsibility of the Aunties and Uncles to communicate the nature of each child’s gifts to the entire community.

And then it is up to the whole community to foster those gifts and develop these talents.”

-Elder(unknown)

Children need to have their gifts, talents and capacities accepted and nurtured as much as possible. Children need to connect to their culture, language and traditional knowledge, and they need opportunities to express creativity and opinions, and freedom from violence, discrimination and racism.

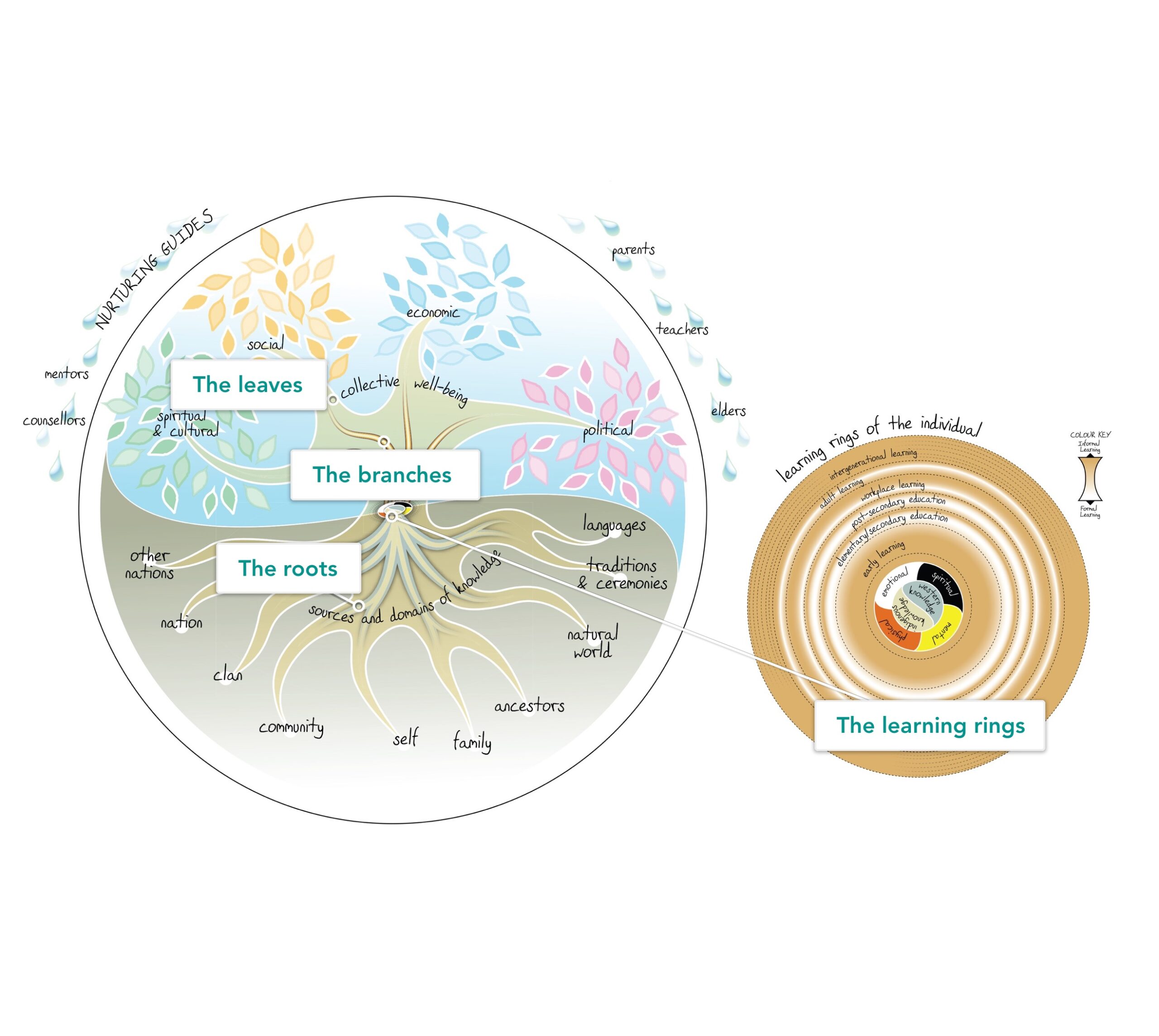

The role of community members in supporting the capacities of young people is also reflected in the First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model. This model views learning as a communal activity involving family, community and Elders, and recognizes that learning occurs throughout one’s life cycle. The First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model is described in Plain Talk 18.

View the First Nations Holistic Lifelong Learning Model

The Leaves

Collective well-being. Growing from each branch is a cluster of leaves, corresponding to the four branches of Collective Well-being–cultural, social, political and economic. Vibrant colours indicate aspects of collective well-being that are well developed.

Collective well-being involves a regenerative process of growth, decay and re-growth. The leaves fall and provide nourishment to the roots to support the tree´s foundation. Similarly, the community´s collective well-being rejuvenates the individual´s learning cycle.

The Branches

Individual well-being. The individual experiences personal harmony by learning to balance the spiritual, physical, mental and emotional dimensions of their being. The model depicts these dimensions of personal development as radiating upward from the trunk into the tree´s four branches; each branch corresponds to a dimension of personal development.

The emotional branch, for example, may exemplify the individual´s level of self esteem or the extent to which he or she acknowledges personal gisfts. Likewise, the intellectual branch may depict the level of critical thinking ability and analytical skills, or level of understanding and use of First Nations language.

The Roots

Sources and Domains of Knowledge. Lifelong learning for First Nations people is rooted in their relationships within the natural world and the world of people (self, family, ancestors), and in their experiences of languages, traditions and ceremonies.

These Sources and Domains of Knowledge are represented by the 10 roots that support the tree (learner), and the Indigenous and Western knowledge traditions that flow from them. Just as the tree draws nourishment through its roots, the First Nations individual learns both from and about the sources and domains of knowledge. Any uneven root growth–expresed, for example, as family breakdown, loss of First Nations language–can destabilize the learning tree.

The Learning Rings

A cross-sectional view of the trunk reveals the seven Learning Rings of the Individual. At the trunk´s core, Indigenous and Western knowledge are depicted as two complementary learning approaches.

Surrounding the core are the four dimensions of personal development–spiritual,emotional, physical, and mental–through which learning is experienced.

The tree´s rings portray how learning is a lifelong process. The rings depict the stages of formal learning, from early childhood through post-secondary education and to adult skills training and employment. However, the rings also show the important role of experimential or informal learning. Learning opportunities are available in all stages of life and across all places of learning such as in the home, on the land, or in the school.

Community engagement encourages young people to explore their potential and acquire the skills, knowledge and attitudes they need to lead satisfying and productive lives. It is the children—the youth—who will become the parents, leaders, workers, Scientists, artists, politicians, healers and innovators of their communities and Nations, and who will determine the direction of the future and the nature of their place in the world.

With skill and knowledge demands steadily increasing in the labour market, education is more important than ever. All members of a First Nations community share the goal of sustaining a society of confident, aware, and educated individuals ready to take their place and responsibilities in the world. All share a vision in which 100% of young people go on to pursue whatever they desire.

Community engagement may require community activism if circumstances are undesirable. There are many things a community can do to take action and make a difference, whether it’s to improve school outcomes or to draw attention to some other community problem. There’s no manual for how to take effective action, but community members must consider a variety of factors.

Role of Elders When Engaging Your Community

For many First Nations, when organizing community gatherings, it is imperative to consider the role of Elders. As seen in Book 8, Cultural Competencies, Elders are community members who have the respect of the people because of their wisdom and knowledge of traditional customs, language and culture, regardless of age or gender. Elders earn this status through their dedication, experience, and understanding of the need to strive for balance and harmony with all living things, and are often consulted on issues in the community.

One of the best ways to approach an Elder, especially if you are from outside the community, is to introduce yourself by telling them your first and last name and giving them background information about who your parents and grandparents are and which community you are from. Then you may present your gift of tobacco and ask the Elder for guidance. This gives the Elder the opportunity to decide if he or she will be your teacher, or if they will refer you to someone else.