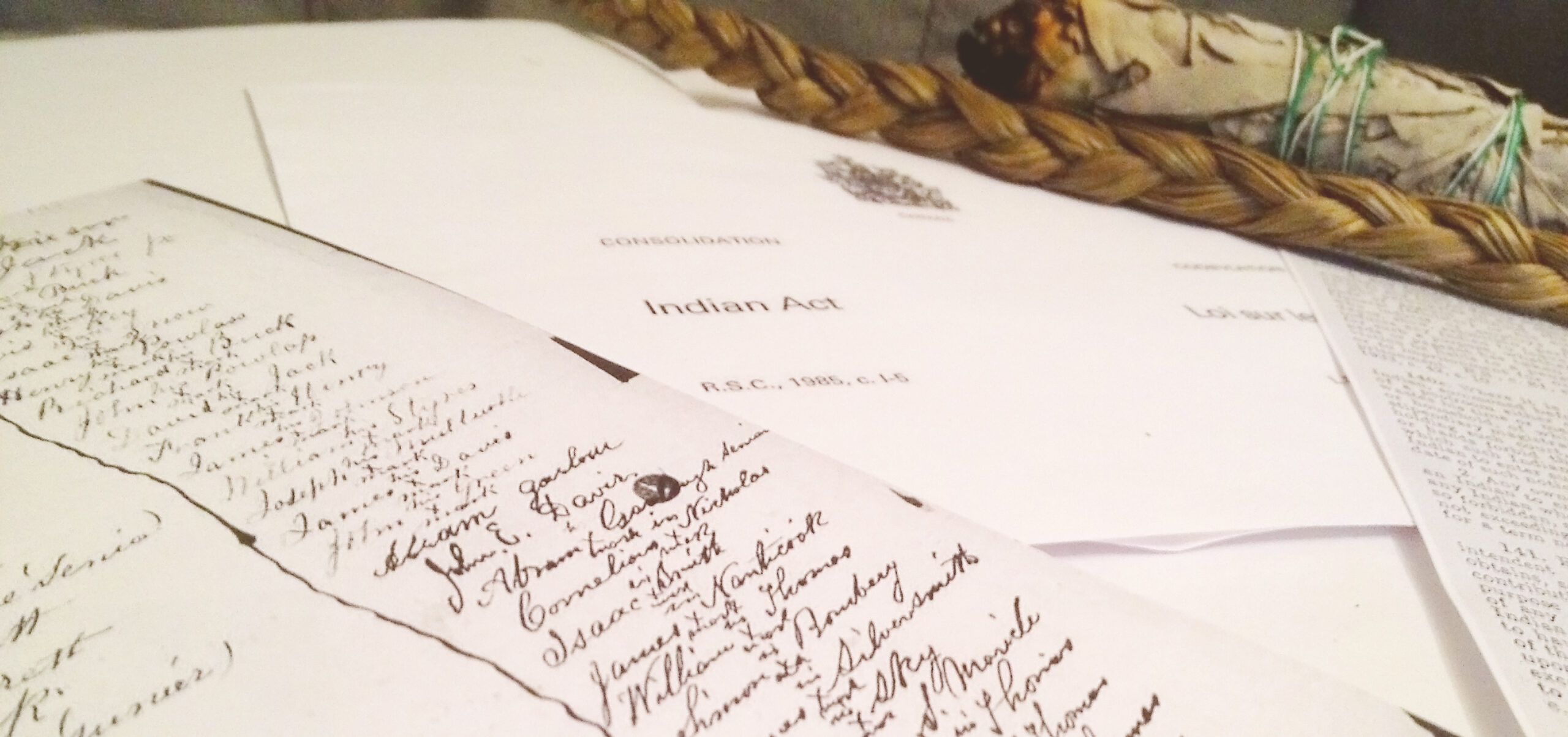

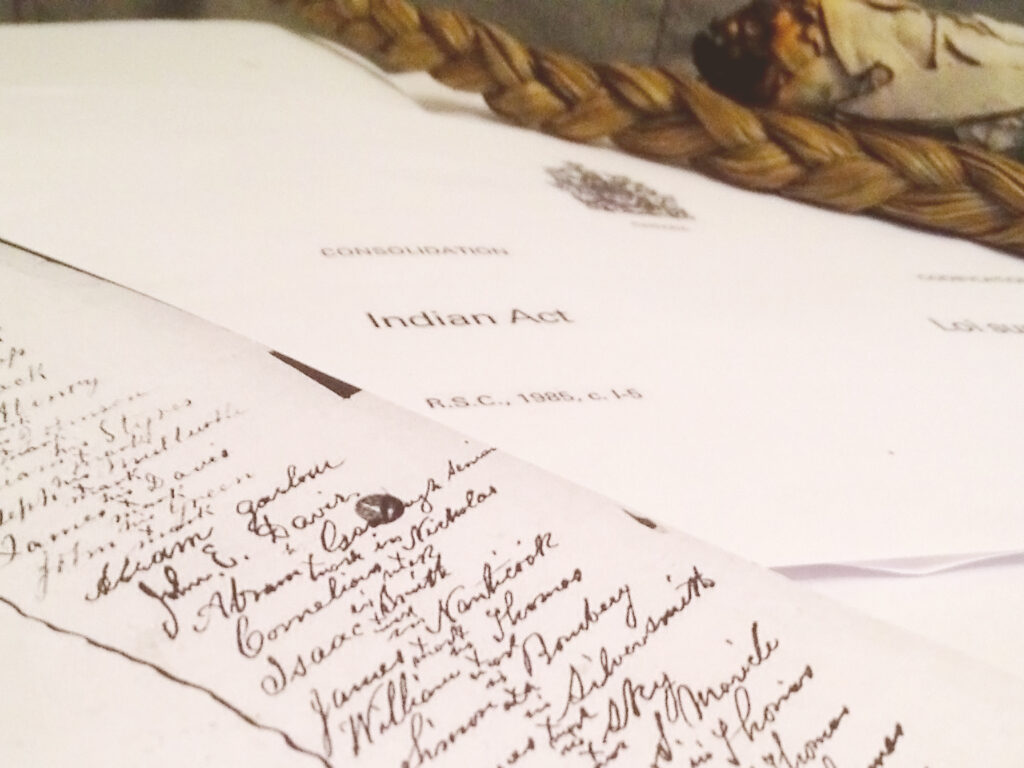

Regulations under the Act

The Indian Act was designed to address “the Indian problem” by singling out a segment of society, largely on the basis of race, removing much of their land and property from the commercial mainstream, and giving the Minister of Indigenous Services Canada and other government officials a degree of discretion that is not only intrusive but frequently offensive.

“We all want to move beyond the Indian Act’s control and reconstitute ourselves as Indigenous peoples and Nations with fundamental inherent rights”

—Assembly of First Nations National Chief Perry Bellegarde

Indian Status

According to the Act, First Nations people (Indians) were deemed not to be people. Right up until 1951, the definition of a person was defined in the statute as an individual other than an Indian. The Indian Act did provide that Indians could become persons by voluntarily enfranchising (giving up their status) and, in many circumstances, they were involuntarily enfranchised by the Act.

Some ways that enfranchisement could happen were by serving with the Canadian Armed forces, attaining post-secondary education, or for a First Nations woman to marry a non-First Nations man.

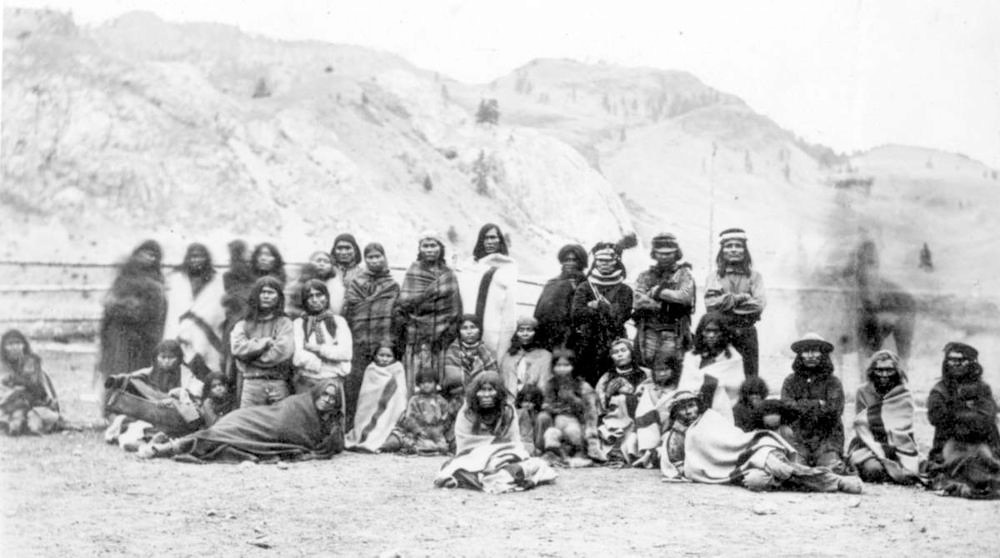

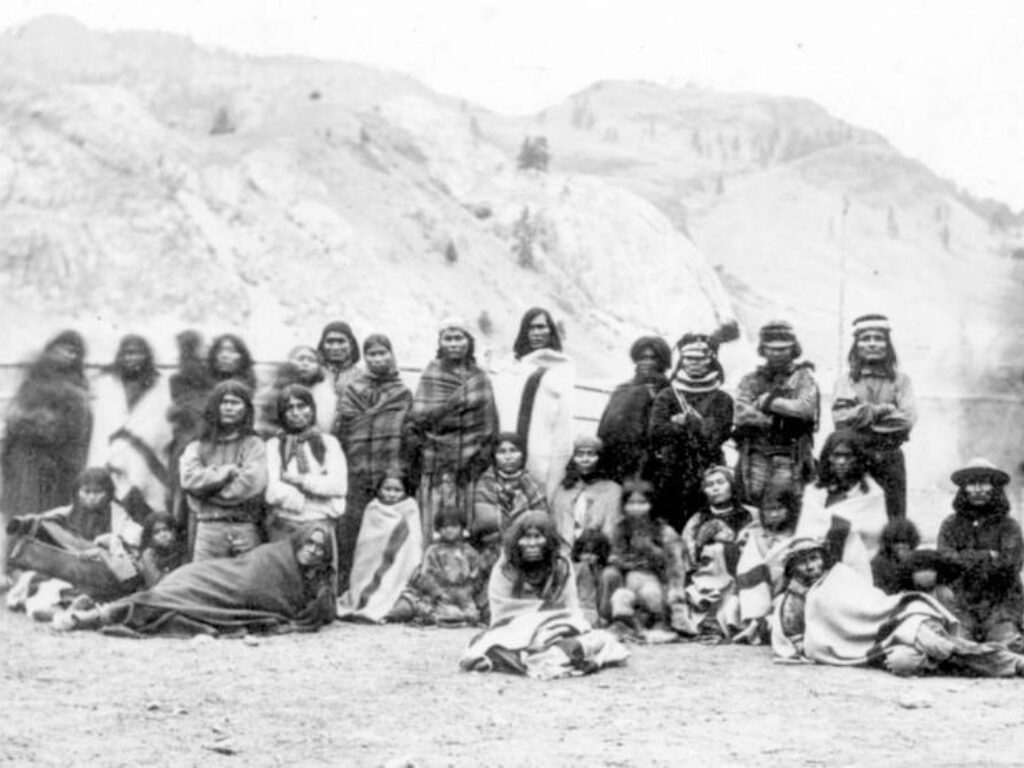

Restriction of Freedoms

The Indian Act placed in the hands of the federal government complete control over First Nations politics, finance, culture, and personal lives. Ceremonies like the potlatch and the Sun Dance that had been practiced for thousands of years were outlawed and forbidden. In 1914, the Act barred the wearing of Aboriginal costume in any dance, show, exhibition, stampede or pageant, unless the Minister approved. The possession of totem poles, grave houses, or even a rock embellished with paintings or carvings was forbidden, unless the Minister approved.

People were not permitted to move about freely, if they did so they could be jailed or fined if, for example, they were deemed to linger in pool halls.

The authority of the Crown even extended to an individual’s Last Will and Testament. A Will could be declared to be void if, in the opinion of the authorities, it was deemed to be unsuitable, inequitable, inferior, unsound, invalid, anything at all.

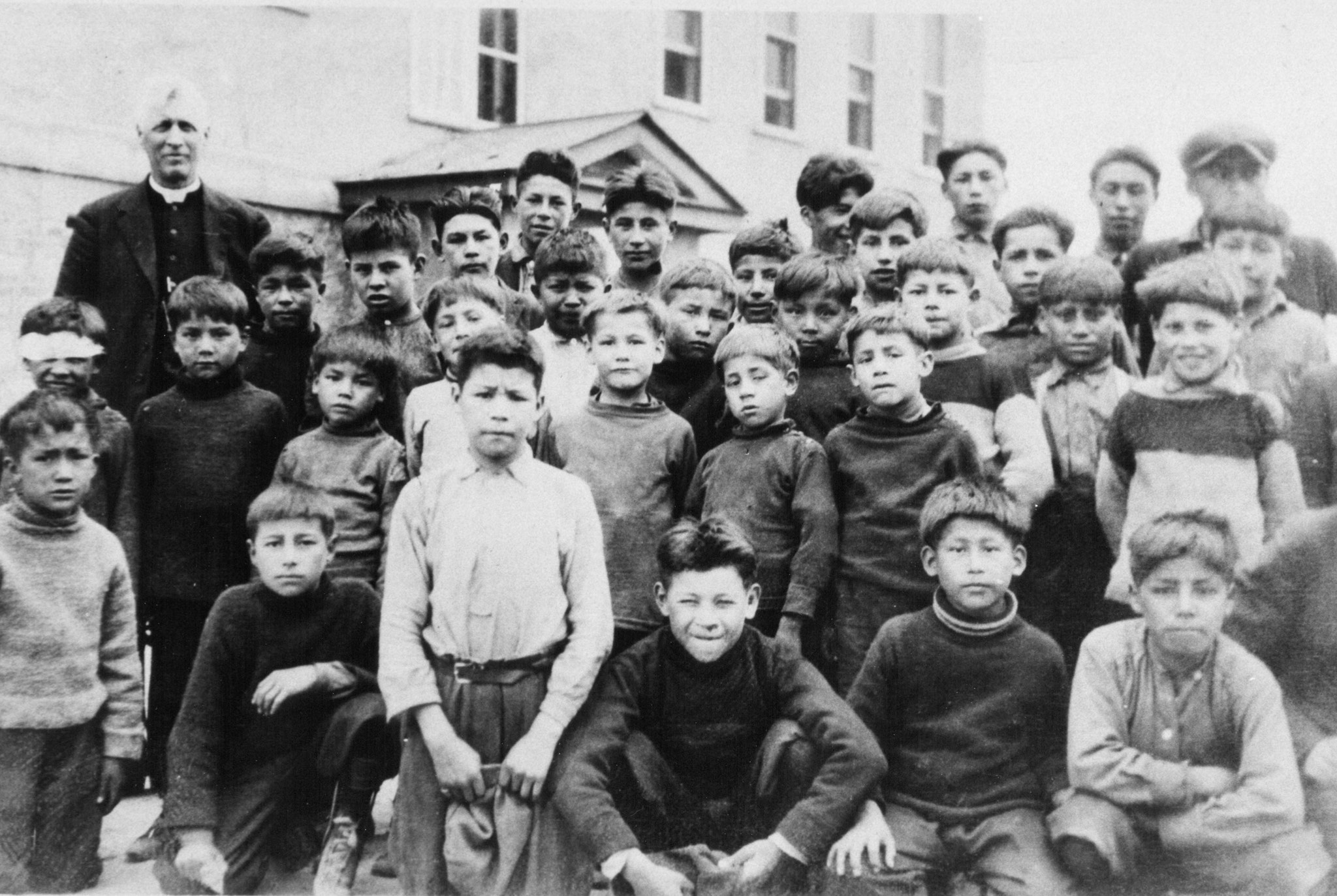

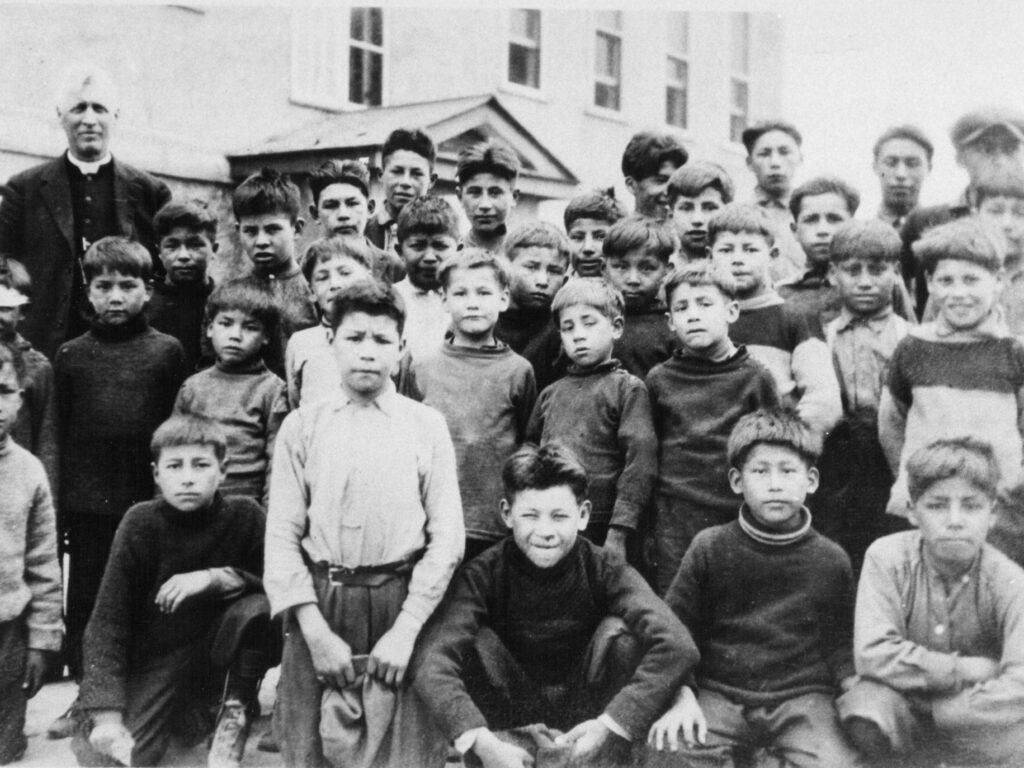

Residential Schools

The Indian Act created Residential Schools and forced a new form of education on First Nations peoples. The decades long strategy of 130 government-funded Residential Schools was to kill the Indian in the child. Under the Act, more than 150,000 children were legally shipped off to institutions where they would have their hair cut, their language killed, their relationships with family and community severed, their sense of belonging destroyed, and their physical, emotional, mental and spiritual health compromised. The Indian Act did provide in minute detail for punishment and consequences. For example when deemed to be Truant, the child could be apprehended and conveyed to school, using as much force as the circumstances require. The Act did not provide for love, support, respect, and caring.

The last of the Residential Schools did not close until 1996. Today, there are an estimated 80,000 former students still living and the catastrophic impacts of the Residential Schools have been, and will continue to be, felt for generations. See Plain Talk 6, Residential Schools.

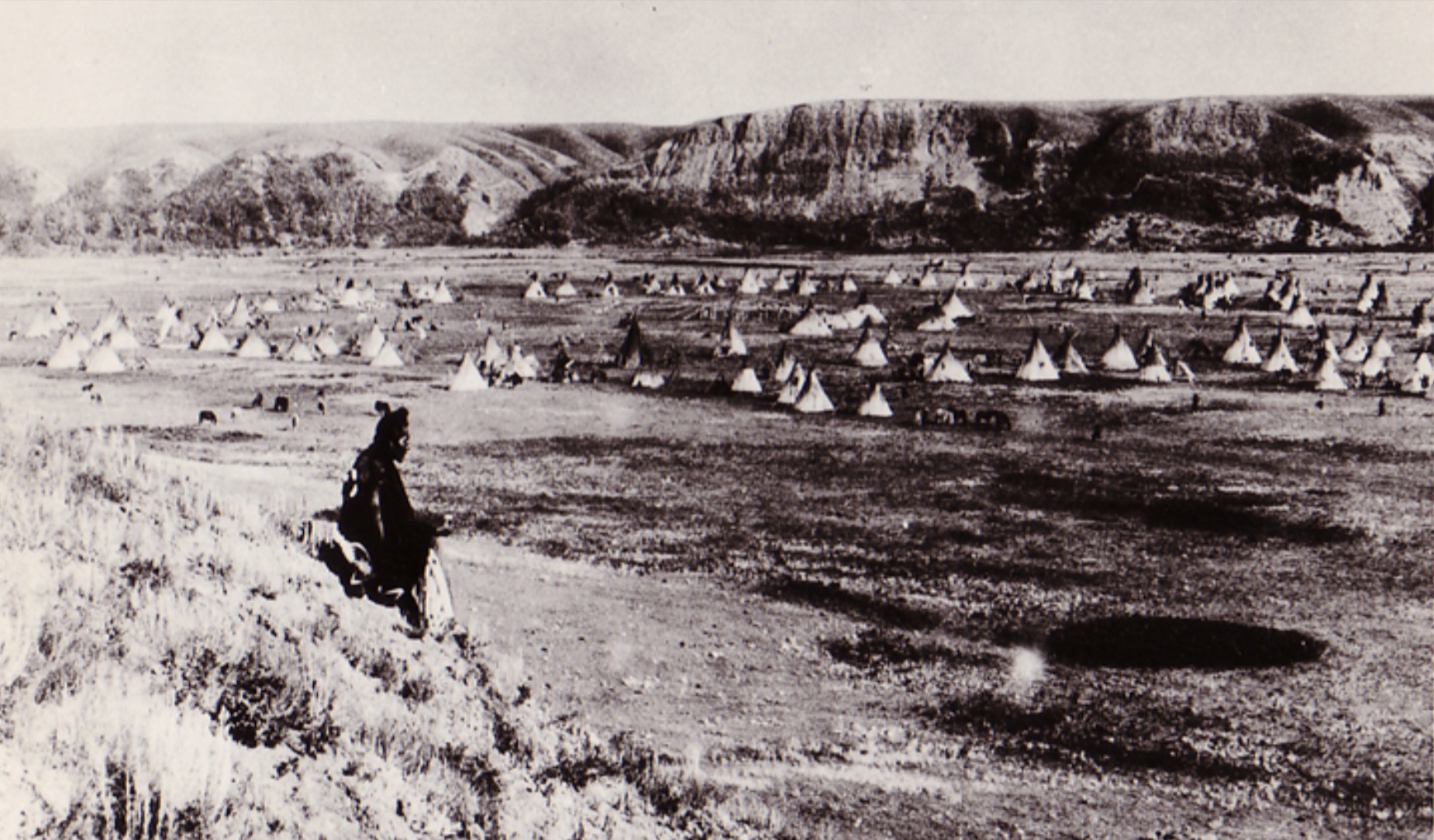

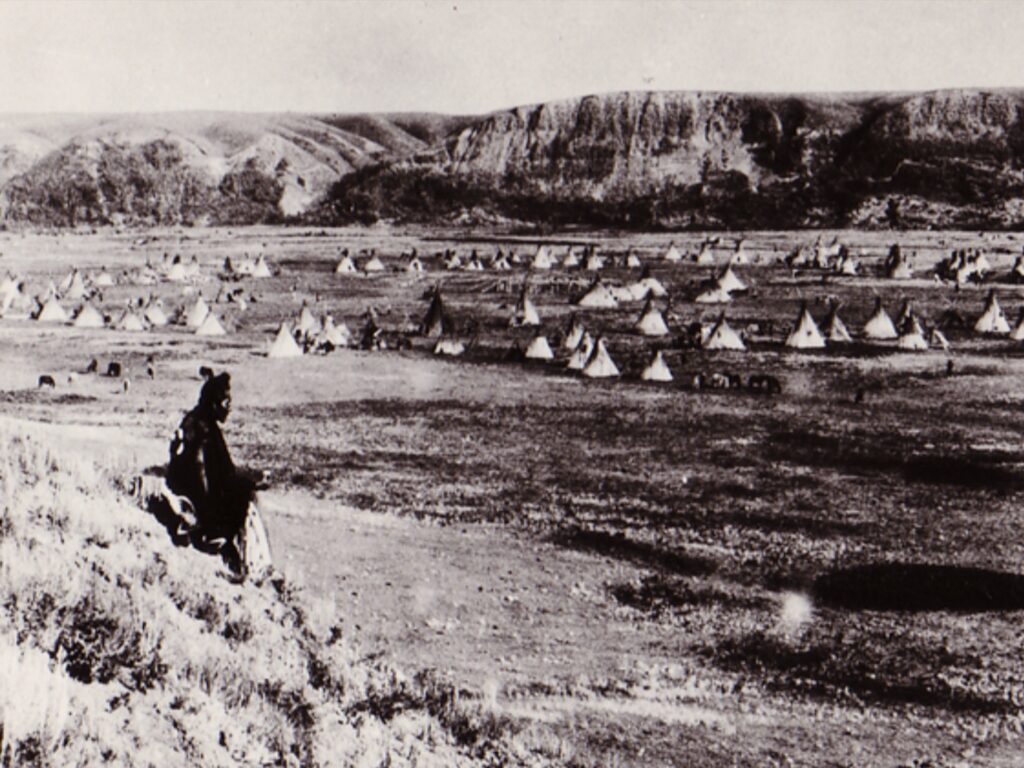

Land

The Indian Act did not allow First Nations people to own land. Over time, measures originally intended to protect the land base were changed to open up reserve lands for farming, settlement, and other purposes by non-First Nations people. The Act set down whether and how land should be cultivated or not cultivated, and whether and how people could buy and sell livestock. It decreed whether and where and how roads should be built and maintained, and where the roads should go, and how fast or slow people could travel on these roads, and even where they could park.

Treaty provisions that permitted the federal government to take up reserve lands for public works of Canada were modified in the Act to allow companies with the power to extract resources to exercise them on reserve. When First Nations people complained of administrative abuses and began to push their claims of Aboriginal title in non-Treaty areas or in areas that were seen as traditional lands, the Act was amended to make it an offence to retain a lawyer for the purpose of advancing a claim. Not surprisingly, the land base was reduced, often in return for nominal consideration or no consideration.

A 1927 amendment required anyone who solicits funds for Indian legal claims to obtain a license from the Superintendent General of Indian affairs. This severely limited the ability of First Nations to pursue land claims through the courts. A major overhaul of the Indian Act in 1951 did see many of these restrictions struck down.

Voting Rights

The Indian Act did not allow First Nations people to vote in a federal election until 1960. Even though for centuries, First Nations people had capably established their own systems of government and managed their own societies and communities, under the Indian Act, First Nations people were not permitted to vote in federal elections. This ban continued until 1960. They could not sit on juries, and they were exempt from conscription in time of war. However, it should be noted that the percentage of volunteers was higher among First Nations people than any other group. One way for First Nations to vote was to surrender up their First Nation Status, or in other words, enfranchise. First Nations were encouraged to enfranchised and even offered incentives such as land.

Amendments

Some amendments have been made to the Indian Act, including lifting of the ban on ceremonies and fundraising, permission to vote, and Bill C-31 to re-establish some First Nations status. Bill C-31 also reinstated those persons and their children who had previously lost status. In the current Indian Act, there is no voluntary or involuntary enfranchisement and marriage is a neutral act: no one gains or loses status based on their gender.

Moving Beyond the Indian Act

The situation has been summarized very well by the lawyer, William Henderson.

The Indian Act seems out of step with the bulk of Canadian law. It singles out a segment of society, largely on the basis of race, it removes much of their land and property from the commercial mainstream, and gives the Minister of Aboriginal Affairs and Northern Development Canada and other government officials a degree of discretion that is not only intrusive but frequently offensive.

The Act has been highly criticized on all sides. Many want it abolished because it violates expected standards of equality. Others want First Nations to be able to make their own decisions as self-governing peoples and they see the Act as inhibiting that freedom. Even within its provisions, people see unfair treatment; for example, First Nations who live on reserve and those who reside elsewhere. In short, this is a statute of which few speak well.

–William Henderson

An argument could be made that the Indian Act should simply be abolished. However, for complex reasons, the sudden disappearance of the Act could create even more problems.

At the 2010 annual meeting of the Assembly of First Nations, National Chief Shawn A-in-chut Atleo called on Ottawa to repeal the Indian Act within five years. He proposed replacing the law with a new arrangement that would allow all parties to move forward on land claims and resource sharing.

Certain nations and organizations, such as the Maa-nulth First Nation, have moved towards Self-Governance agreements. Though these do not exempt First Nations from the Indian Act, it allows more autonomy for the nations to make decisions about their education, economy, resources etc.