Residential School Experiences

For almost their entire history, residential schools were run by religious organizations— Christianity’s Roman Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian, United and Methodist Churches. Their missionaries, ministers, priests and nuns administered the schools, taught the classes, and looked after the students all within a Christian framework. Many of these people were sincerely devoted to making a positive change in the lives of their students, although overwork, poor pay, isolation and colonial attitudes took their toll on the quality of education and on the well-being of the students. As part of the assimilation process, students were forbidden to respect or continue their First Nations customs, traditions and languages.

The federal government provided most of the funding for residential schools. However, as the system grew and expanded, there were continuing reductions, leading to severe underfunding for much of the time. From the beginning of the residential school system, federal politicians were aware of the problems caused by inadequate funding and poor instruction, but such observations were suppressed and ignored.

Students typically attended these schools for 10 years or more. They were usually taken from their homes at five years of age, and generally finished school at age 15. Some students were able to go home for the summer, but it wasn’t uncommon for students to remain at residential school for the entire duration of their schooling years and not ever see or visit their parents and family members and community.

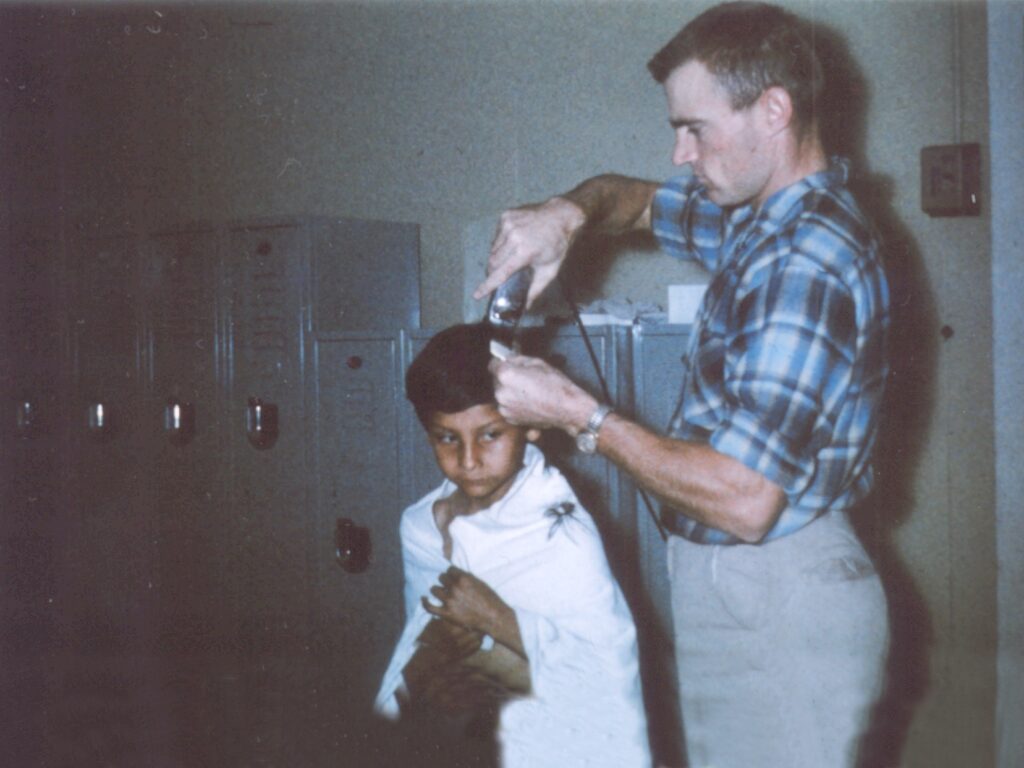

When youth arrived at their residential school, they were stripped of their First Nations identity. Possessions and clothing were taken away. Youth were assigned uniforms. Their First Nations name was abandoned and replaced with a Christian name. While at the schools, students were deprived of their First Nations heritage—language, customs, and spirituality—without being provided with a sustainable and viable alternative.

Listen to this clip, from the Wawahte documentary, of one former student's story.

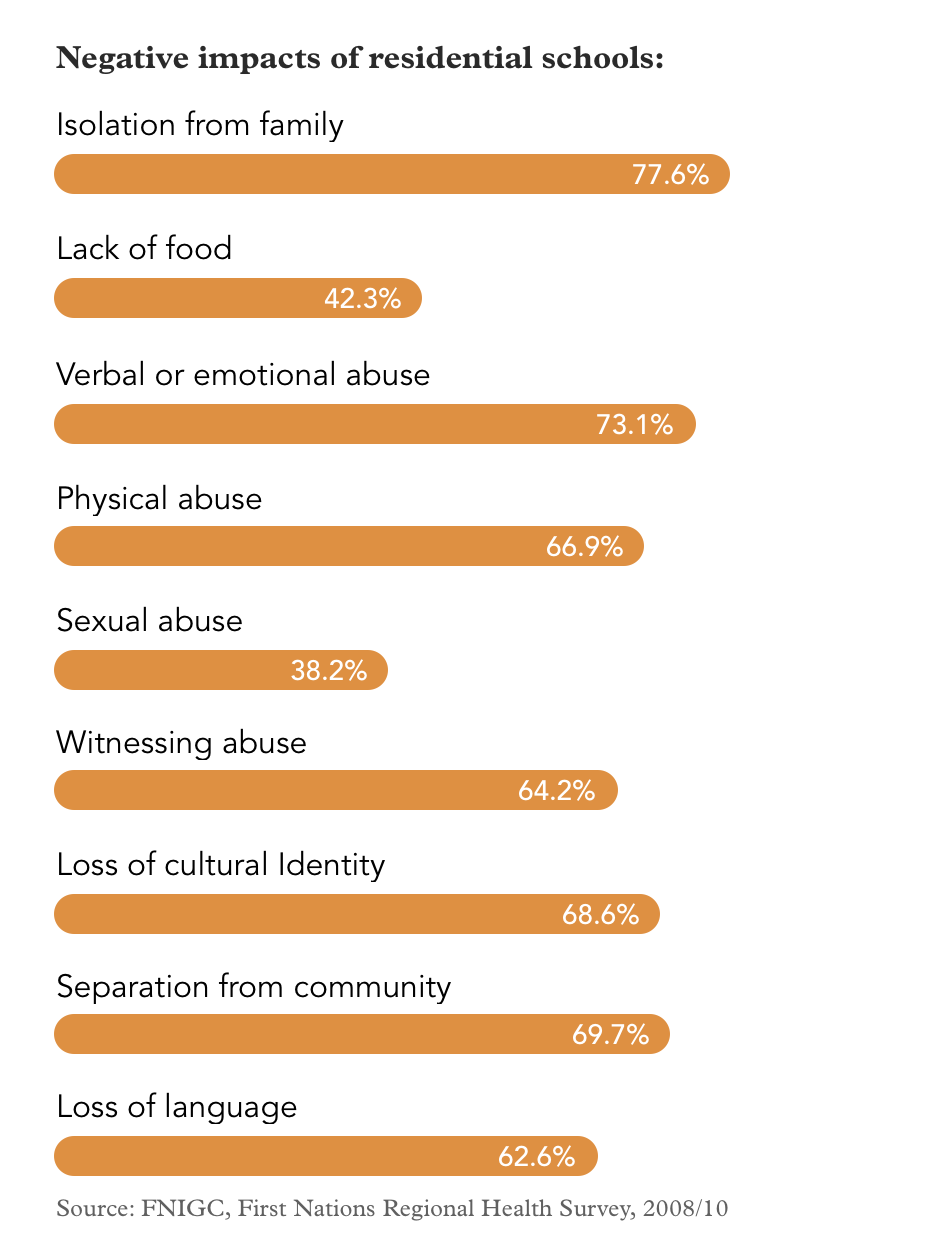

Some students had positive experiences and received decent educations. However, many students were subjected to or witnessed a wide range of indignities, including humiliation and nutritional, physical, psychological, and sexual abuse. In addition, because visits by family and community members were rare and often forbidden or impossible, students experienced feelings of loneliness and isolation. Not surprisingly, students were susceptible to disease and poor health. Suicide was not uncommon.

Listen to this clip, from the Wawahte documentary, of one former student's story.

To reduce costs of operation, some residential schools exploited the students by requiring that the students work for half the day, thereby limiting the time available for education. Funding limitations also affected the quality of education. Many of the teachers at residential schools were not properly trained, lacking professional certification and qualifications. Poor housing conditions caused by inadequate funding adversely affected student safety and well-being. It is estimated that up to 50% of students who attended residential schools died there!

Listen to this clip, from the Wawahte documentary, of one former student's story.

How did residential school students fare as adults?

Residential schools were created and designed to prevent students from acquiring the skills, knowledge, attitudes and understandings of their First Nations culture. First Nations youth attending residential schools were deprived of their families, communities, and heritage. The residential school experience prevented students from learning the traditional ways and patterns of their culture—the customs, stories, ideas, language, spirituality, ethics, morality, language, etc. The Indian Act compounded these losses by declaring it illegal for First Nations to take part in sacred ceremonies like the Potlatch and Sun Dance. Added to the cultural interference was the humiliation, deprivation and abuse many First Nations youth encountered in residential schools. Many students who had attended residential schools subsequently had profound identity problems, confused about who they were and their place in their First Nations culture and in the wider Canadian culture.

Listen to this clip, from the Wawahte documentary, of his story.

How did residential schools affect others?

Residential school experiences have had profound effects on other members of First Nations communities. These effects have come to be known as the “intergenerational legacy” of the residential school system, influences that have been passed on from generation to generation. This intergenerational legacy has been described as the “effects of physical and sexual abuse that were passed on to the children, grandchildren and great-grandchildren of Indigenous people who attended the residential school system.” From an Indigenous perspective, these effects are expressed in the mental, emotional, physical and spiritual dimensions of the Indigenous life experience.

“We were made to feel ashamed for having been born Indian.”

— Esther Love (Faries) Residential School Survivor

When did the general public learn about residential schools and their problems?

It wasn’t until the 1990s that the general public became aware of how the events at residential schools had impacted generations of First Nations communities. Although problems of disease, hunger, overcrowding, staff training, low quality of education and building disrepair had been pointed out long ago, little or nothing had been done for decades.

Former students of residential school, who came to be known as “Survivors” of residential schools, reported their own experiences. Finally the media and politicians paid attention. A period of lawsuits and hearings resulted in the Indian Residential Schools Settlement Agreement (IRSSA), the largest class-action settlement in Canadian history. In addition to providing financial compensation to residential school Survivors, the Agreement established the Indian Residential Schools Truth and Reconciliation Commission to document the real events at residential schools and make that information available to all Canadians. The Commission’s purpose was to “guide and inspire First Nations, Inuit and Métis peoples and Canadians in a process of truth and healing leading toward reconciliation and renewed relationships based on mutual understanding and respect.”

Read the Indian Residential School Settlement Agreement.

pdf • 398 KB