What are Residential Schools

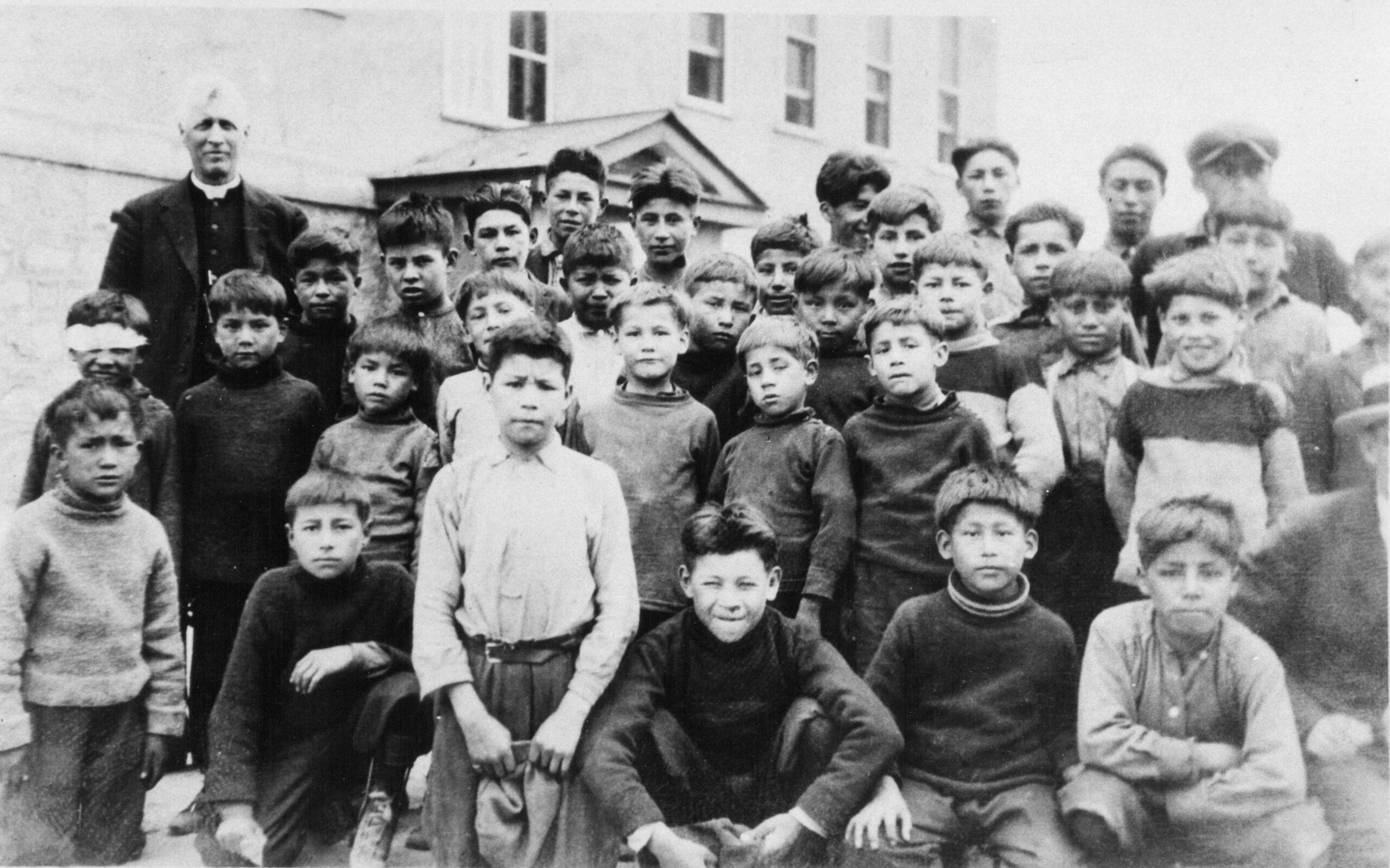

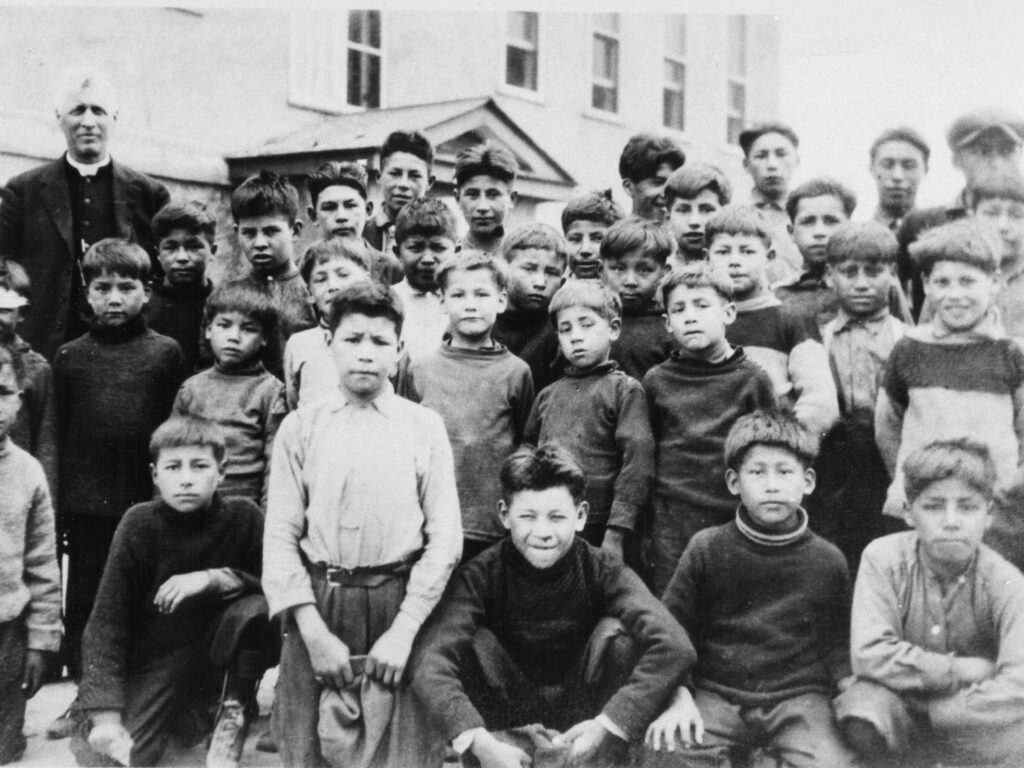

Residential schools were boarding schools for Indigenous (First Nations, Inuit and Métis) children and youth, financed by the federal government but staffed and run by several Christian religious institutions— the Roman Catholic, Anglican, Presbyterian, United and Methodist Churches. Children were separated from their families and communities, sometimes by force, and lived in and attended classes at the schools for most of the year. Often the residential schools were located far from the students’ home communities.

How long did residential schools exist

From their start in the 1800s until the last one closed in 1996, about 130 residential schools operated in every province and territory in Canada, except for the provinces of New Brunswick, Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland. During this period, over 150,000 Indigenous youth were enrolled in residential schools. Enrollment reached a peak about 1930, with over 17,000 students in 80 schools. As of 2012, about 93,000 Indigenous adults who attended residential schools were still alive to tell their stories and describe their experiences.

Explore the residential schools history timeline from 1620 onwards.

A number of factors laid the foundation for the creation of residential schools:

The dominant European mentality and view of Canada’s original inhabitants was racist and backwards. The federal government considered it necessary to “assimilate” Indigenous people, and to have Indigenous nations conform to the European/Canadian customs, attitudes and ways of dressing, believing, behaving and working. Some politicians (and others) of the time sought to “kill the Indian in the child” and “civilize” Indigenous youth by separating them from their heritage and customs and indoctrinating them to European and Christian ways. This false, misguided and racist perspective denied and rejected the validity of First Nations languages, customs, spirituality and traditions. The main reason for these assimilationist policies was for land and resource exploitation. Dispossession and extinguishment of rights would also help to ensure the establishment of Canada as a legitimate nation state.

In 1876, the federal government introduced the Indian Act. Under the Act, the federal government took control of all aspects of the lives of First Nations people, including their means of governing themselves, their economies, religions, customs, traditions, land use and education. The Indian Act includes criteria and a definition of who is an “Indian.”

First Nations leaders supported education of their young. They recognized that providing their youth with the skills and knowledge relevant to the times would be important in the adaptation of their Nations and communities to the new situations arising from the presence of European settlers. However, the idea of separating children from their communities to attend school was not supported by parents and Elders.

First Nation leaders always insisted that schooling should be within, not distant from, their communities.

Treaties with First Nations obligated governments to fund the education of First Nations youth.

Residential schools were the federal government’s way of meeting their treaty commitments to education.

Indigenous people were considered to be a “problem” because their presence was getting in the way of the continuous expansion of settlement and exploitation by the European powers. Assimilation and absorption of Indigenous people into the “mainstream” were considered to help eliminate the “problem.

Christian missionaries considered it their duty to convert the First Nations to what they considered to be the only true religion, Christianity.

Map of residential schools recognized under the IRSSA