Treaties and Why They are Important

The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, 1969, defines a treaty as “an international agreement concluded between States in written form and governed by international law, whether embodied in a single instrument or in two or more related instruments and whatever its particular designation.”

The Supreme Court of Canada, in R. v. Sioui, 1990, noted “What characterizes a treaty is intention to create obligations, the presence of mutually-binding obligations and a certain measure of seriousness. Section 35 of the Constitution of Canada recognizes and affirms Rights arising from treaties, however, as you will read later, there is often disagreement between the Crown and First Nations over the interpretation of treaties.

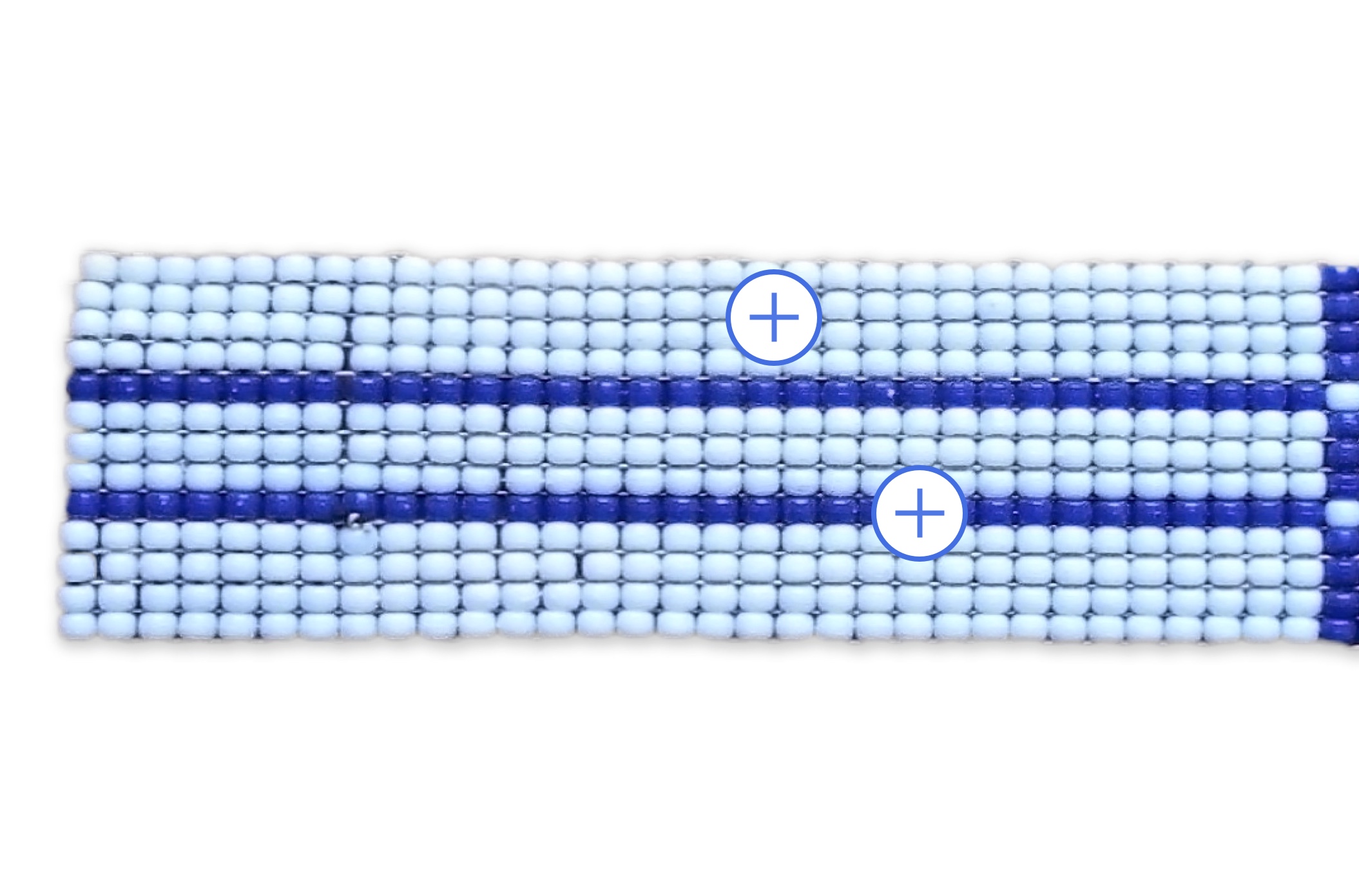

First Nations devised their own distinctive and creative ways to record a significant event like a treaty. One way was the oral transmission from generation to generation by the telling of stories by Elders and other members of the communities. Another way to record a significant event was by weaving a Wampum Belt, used by the Haudenosaunee as a visual record of an agreement. Wampum Belts commemorated events and agreements with other nations, told stories, and described customs, histories or laws. They are not a form of writing. Rather, wampum belts are visual symbols that serve a mnemonic or memory-boosting purpose—a wampum belt triggers and stimulates the reader’s memories of the significance and meaning of the details woven into the belt.

The Wampum Belt pictured below is known as the Kaswentha or Two Row Wampum Belt. This Belt is significant because it embodies the concepts and principles that were the basis of all the Haudenosaunee (Iroquois) agreements or treaties with other nations, including the Dutch, French, and English settlers. The Two Row Wampum Belt is a visual record and statement of the cultural, political, and economic sovereignty maintained by the Haudenosaunee in their treaty with representatives of the Dutch government in 1613 and the basis for later agreements with the Dutch (1645), French (1701) and English (1763-64). The handwritten copy of the Kaswentha was translated from Dutch by Dr. Van Loon.

The Two Row Wampum Belt

The Two Row Wampum Belt contains two parallel rows of dark (purple) beads separated and surrounded by rows of light (white) beads. The meaning of the Two Row Wampum Belt is as follows:

We will travel the river together, side by side, but in our own vessel. Neither of us will make compulsory laws nor interfere in the internal affairs of the other. Neither of us will try to steer the other’s vessel.

As long as the Sun shines upon this Earth, that is how long our Agreement will stand—as long as the Water still flows—as long as the Grass grows green at a certain time of the year. We have symbolized this Agreement and it shall be binding forever as long as Mother Earth is still in motion.

Light Beads

The white beads are considered to represent peace, friendship and respect.

Dark Beads

The two rows of dark beads represent two nations in separate vessels moving in a body of water like a river.

Learn about The Two Row Wampum Belt:

Treaties are part of the heritage of First Nations peoples, who entered into a variety of agreements with other First Nations for purposes like sharing lands for hunting and trapping long before the arrival of Europeans in North America. The most famous of these was the Great League of Peace— Kaianere’kó:wa or the Constitution of the Five Nations (the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga, Oneida and Mohawk people) to live together in peace by forming the Iroquois Confederacy or Haudenosaunee. The agreement was based on democratic ideas that respected the integrity and sovereignty of the member Nations. On October 21, 1988, the 100th Congress of the United States, Resolution 331, acknowledged the contribution of the Iroquois Confederacy to the development of the United States Constitution.

“It is high time that the government stops trying to do things for us and starts doing things with us.”

—Chief Atleo

![The image displayed here is the symbol of the Five-Nations Haudenosaunee [Iroquois] Confederacy, and is otherwise known as the Hiawatha Wampum.](https://education.afn.ca/afntoolkit/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/book_4_1_1_five_nations-1024x768.jpg)

Listen to the Story of the Peacemaker

Beginnings of European-First Nations Interaction

From time immemorial, Indigenous peoples lived and thrived throughout North America. The original peoples had adapted to the diverse landscape, geography and climate of the continent, and evolved complex cultures, languages, customs, religions, medicinal care and creation stories tied to their strong association and connection with the land. The different Indigenous nations were intimately familiar with the land they inhabited, land that supported them, and which, in turn, they revered and respected. The original inhabitants traded, waged war and made peace with each other, and acquired the skills,knowledge, tools and understandings appropriate to their environment, their customs, history and culture.

From the time of their first arrival in North America, European nations worked out a number of different arrangements with the First Nations. The earliest arrangements were peace and friendship treatiesand informal trading agreements between English, French, Portuguese, Irish, Spanish, Basque, and Breton fishermen and First Nations of the east coast (primarily Mi’kmaq and Maliseet). European explorers and settlers, unfamiliar with the different conditions in North America, owed their very existence to the expertise of the Indigenous peoples. However, Europeans sought to increase their wealth and influence in North America and began to establish colonies and settlements which was encouraged by their own countries. By the 1700s both the British and French became the dominant colonial powers.

To strengthen their commercial interests (a significant part of which was the fur trade), the British and the French developed various types of agreements and alliances with First Nations. For example, from 1725 to 1779, the British entered into a number of “Peace and Friendship” treaties with the Mi’kmaq, Maliseet, and Passamaquoddy peoples in what are now New Brunswick and Nova Scotia. The British colonial administration expected that these treaties would end hostilities between the British and the First Nations and establish ongoing peaceful relations. Included in these treaties were assurances that First Nations could continue to trade with the British, and hunt, fish, and observe traditional customs and religious practices. No First Nations land was surrendered in these treaties.

The British and French colonial powers expanded their influence from the east coast into the interior of North America by exploiting and developing the long-established First Nations trade routes. What followed were conflicts with each other and First Nations, the building of European forts and posts, and the forging of various alliances and agreements with First Nations.

Military conflicts between the French and British (also involving their First Nations allies) were common, reaching a critical point in 1760. French colonial efforts ended when Montréal, the last French colony on the St. Lawrence River, fell to the British. To consolidate British power, and to ensure peaceful relations with First Nations, the British created a series of treaties between themselves (known as “The Crown”) and First Nations communities.

Later Treaties

In 1763, a document titled the Royal Proclamation contained a number of significant provisions. It integrated the French territories into the new Province of Québec. The Royal Proclamation also specified that future negotiations with First Nations were to be between First Nations and representatives of the British crown, not with private individuals, and that these negotiations would take the form of written treaties. Furthermore, many view the Royal Proclamation as the first legal instrument unilaterally issued by the Crown that recognizes the fundamental rights of First Nations to their lands and resources, and their sovereignty.

A series of treaties were signed after the Royal Proclamation: the Upper Canada Treaties (1764 to 1862) and the Vancouver Island Treaties (1850 to 1854). The American War of Independence and the creation of the United States of America resulted in the British assigning land to a flood of immigrant British loyalists from the new United States of America and to First Nations allies of Britain who lived in the new country during the American War of Independence. The need for more land caused the British to exert greater pressure on First Nations.

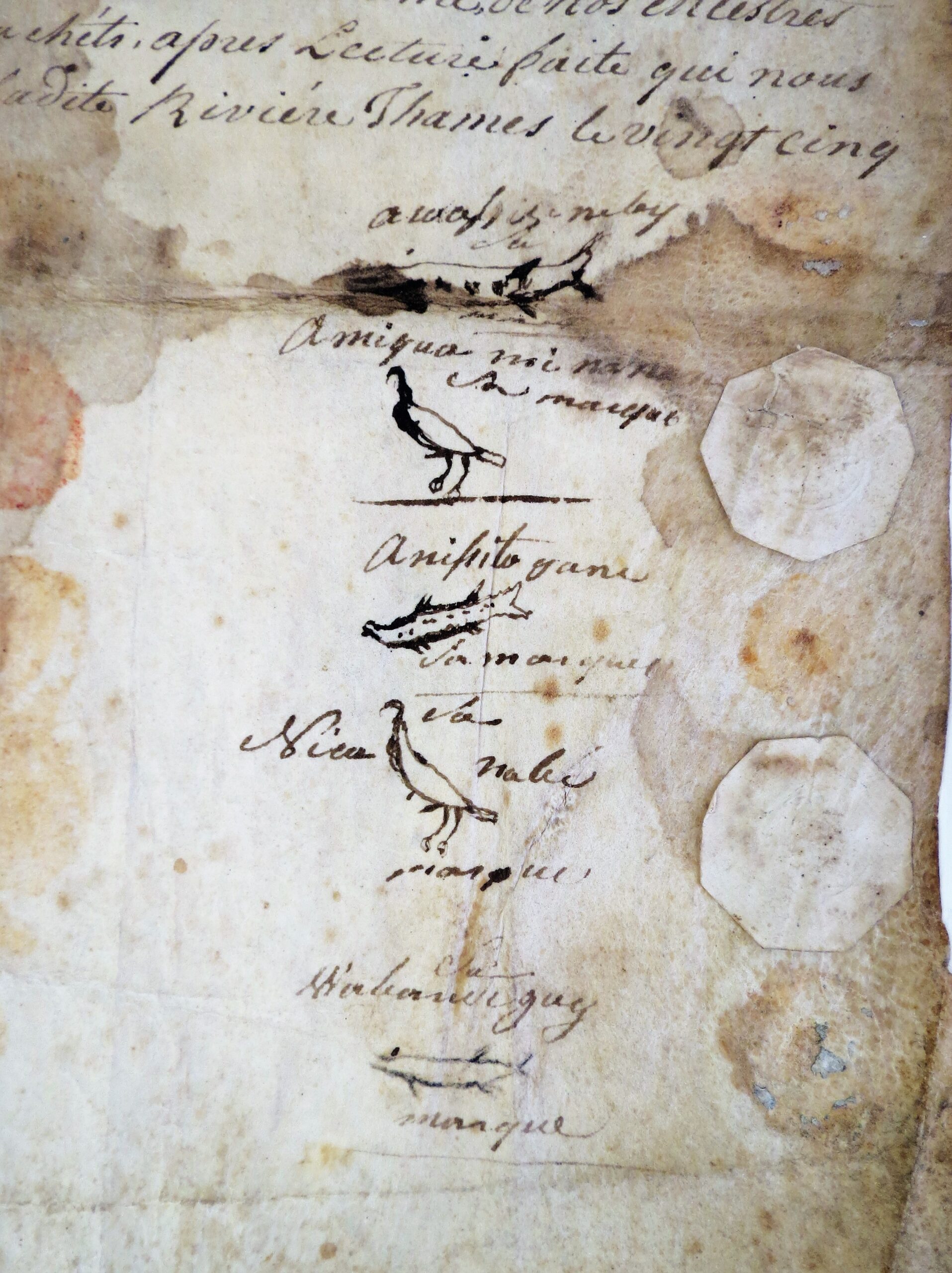

View the Chiefs signatures on the treaty with the Chippewa, October 4, 1842.

pdf • 2 MB

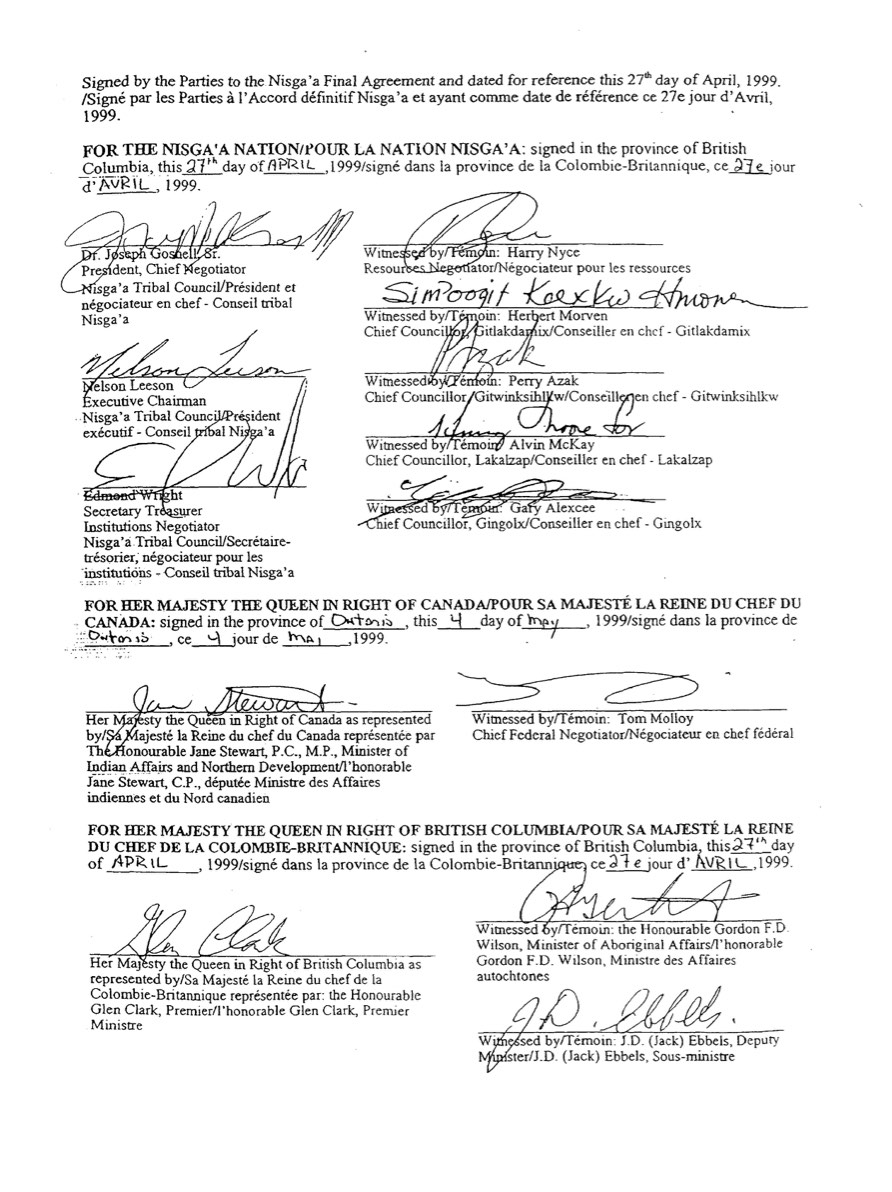

By the 1830s, First Nations found themselves forced into small remnants of their original territories that were economically unsustainable, with limited opportunities for growth, and increasingly losing access to medicinal plants and food, and hunting and fishing grounds. From 1871 on, the Canadian government signed treaties with First Nations for the development of farming and resource exploitation in the west and north of the country. These particular treaties have come to be known as the Numbered Treaties associated with Northern Ontario, Manitoba, Saskatchewan, Alberta and parts of the Yukon, the Northwest Territories and British Columbia.

Shape

The medal is a circle that represents a coming together of two nations. The circle is sacred because it imitates Creation.

Shaking Hands

One person on this medal represents the Crown while the other represents the First Nations. They’re not only shaking hands but holding hands making a promise to each other. Both men are standing on equal ground, each respecting each other.

Teepees

Many teepees represent many different First Nations.

Sun and Grass

The symbols of Creation are represented by water, sun and the grass where the teepees stand. It is commonly said that the treaties will last “for as long as the sun shines, the grasses grow and the rivers flow.”

Hatchet

The hatchet buried on the ground acknowledges treaties are about peace and living together in harmony.

The medal is a circle that represents a coming together of two nations. The circle is sacred because it imitates Creation.

One person on this medal represents the Crown while the other represents the First Nations. They’re not only shaking hands but holding hands making a promise to each other. Both men are standing on equal ground, each respecting each other.

The symbols of Creation are represented by water, sun and the grass where the teepees stand. It is commonly said that the treaties will last “for as long as the sun shines, the grasses grow and the rivers flow.”

The hatchet buried on the ground acknowledges treaties are about peace and living together in harmony.

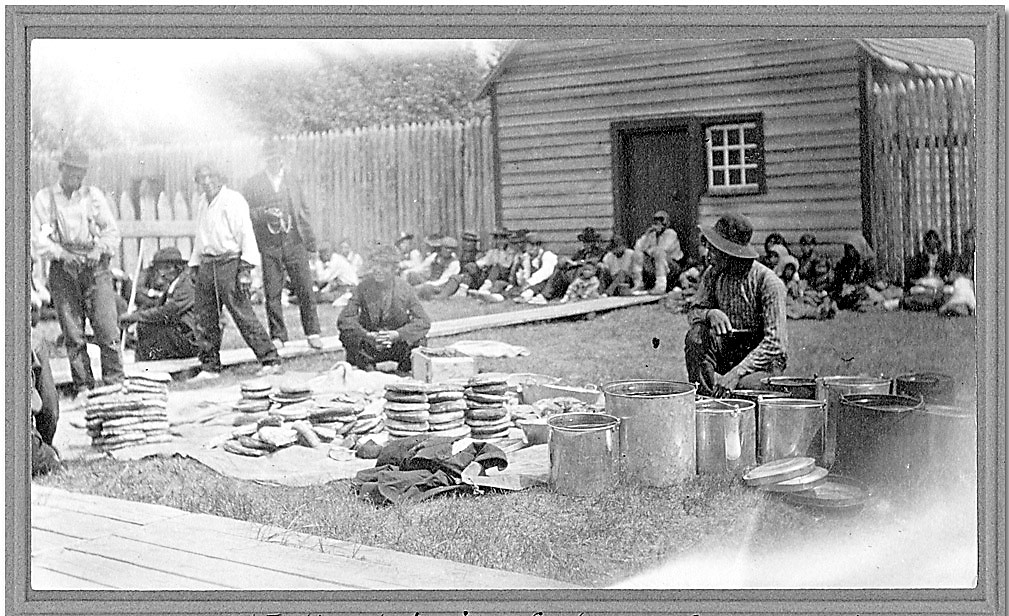

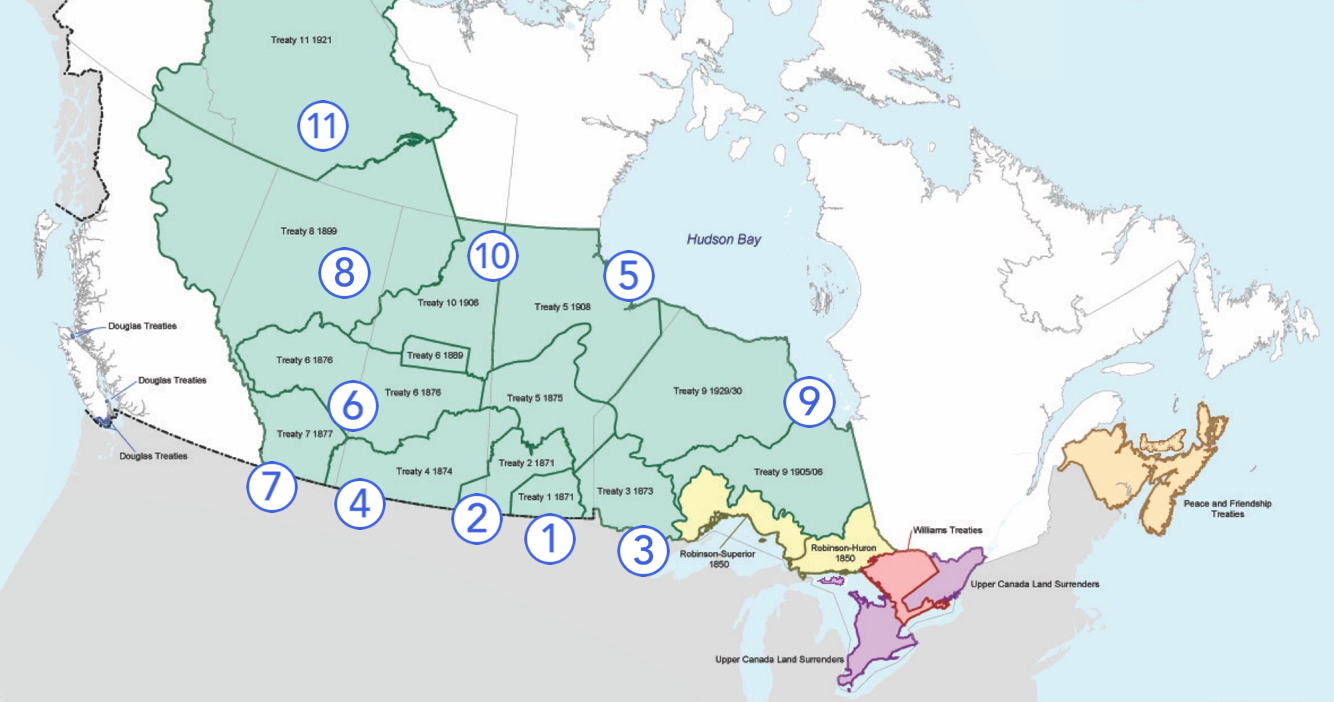

The Numbered Treaties (1-11): 1871-1921s

![Women and children [of Brunswick House First Nation] at the feast during Treaty 9 payment ceremony at [the Hudson’s Bay Company Post called] New Brunswick House, Ontario.](https://education.afn.ca/afntoolkit/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/book_4_1_1_treaty-brunswick-1024x768.jpg)

As required by the Royal Proclamation of 1763, the British Crown, through their representatives of the Dominion of Canada, were obliged to enter into formal treaty processes before they could expand westward. The British Crown and First Nations interpreted the meaning and intention of treaties in drastically different ways.

The British Crown considered the Numbered Treaties to be an exchange for the surrender of Indigenous Rights and Title to land, so settlers from foreign lands could occupy lands within the colonial territories that the British laid claim to. In return, the British Crown guaranteed First Nations certain Treaty and Inherent Rights in perpetuity.

First Nations that signed these Numbered Treaties believed they were entering a trust relationship with the British Crown; First Nations were to share and co-exist with settlers from foreign lands. Therefore, First Nations never agreed to the sale of their lands and resources. Instead, they agreed to share their Indigenous lands, to the depth of a plough, as stated in the following quote:

“At the time, the government said that we would live together, that I am not here to take away what you have now…I am here to borrow the land…to the depth of a plough…that is how much I want.”

Based upon First Nations oral histories and written documentation, including that of the actual written text of the Numbered Treaties, First Nations assert that the British Crown made the following promises when the Numbered Treaties were negotiated and signed, which have come to be known as First Nations Treaty and Inherent Rights.

- The Treaty & Inherent Right of First Nations to maintain their own systems of governance, including selection of leadership and control over own citizenship, trade and spiritual beliefs.

- The Treaty & Inherent Right to Shelter.

- Treaty annuity or annual payments under the terms of certain treaties.

- The Treaty & Inherent Right to Child Welfare.

- The Treaty & Inherent Right to Land and Resources.

- The Treaty & Inherent Right to Health.

- The Treaty & Inherent Right to Education.

- The Treaty & Inherent Right to Hunting, Fishing, and Trapping.

- The Treaty & Inherent Right to Justice.

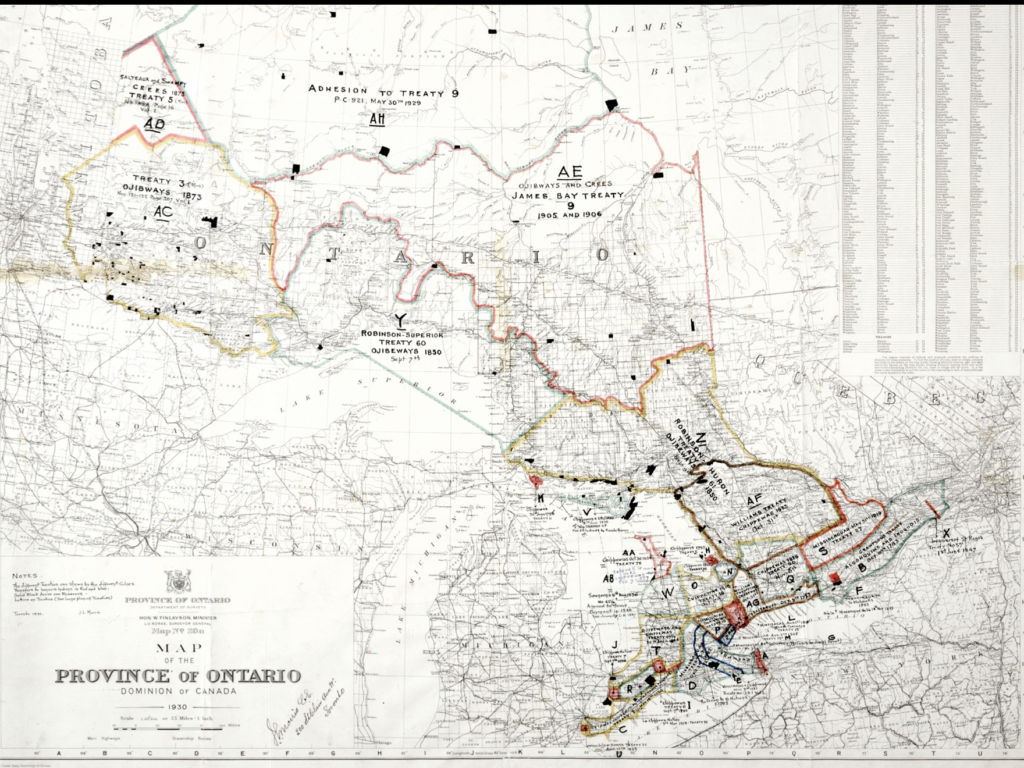

Treaties 1-11 (Traditional Territory/Current Context)

Treaty 1: Southern Manitoba

Treaty 2: Southern Manitoba

Treaty 3: Southern Manitoba, Central Ontario

Treaty 4: Southern Manitoba, Southern Saskatchewan, Central Manitoba

Treaty 5: Central and Northern Manitoba

Treaty 6: Central Alberta, Central Saskatchewan

Treaty 7: Southern Alberta

Treaty 8: Northern British Columbia, Northern Alberta, Northern Saskatchewan

Treaty 9: Northern Ontario, Northern Manitoba

Treaty 10:

Treaty 11:

Treaty 1: Southern Manitoba

Treaty 1: Southern Manitoba Treaty 2: Southern Manitoba

Treaty 2: Southern Manitoba Treaty 3: Southern Manitoba, Central Ontario

Treaty 3: Southern Manitoba, Central Ontario Treaty 4: Southern Manitoba, Southern Saskatchewan, Central Manitoba

Treaty 4: Southern Manitoba, Southern Saskatchewan, Central Manitoba Treaty 5: Central and Northern Manitoba

Treaty 5: Central and Northern Manitoba Treaty 6: Central Alberta, Central Saskatchewan

Treaty 6: Central Alberta, Central Saskatchewan Treaty 7: Southern Alberta

Treaty 7: Southern Alberta Treaty 8: Northern British Columbia, Northern Alberta, Northern Saskatchewan

Treaty 8: Northern British Columbia, Northern Alberta, Northern Saskatchewan Treaty 8: Northern Ontario, Northern Manitoba

Treaty 8: Northern Ontario, Northern Manitoba Treaty 9: Northern Ontario, Northern Manitoba

Treaty 9: Northern Ontario, Northern Manitoba Treaty 10: Northern Saskathewan, Central Alberta

Treaty 10: Northern Saskathewan, Central Alberta Treaty 11: Northwest Territories, Yukon Territory

Treaty 11: Northwest Territories, Yukon Territory

Unceded Territory

![British Columbian Siwashes. Lilloett, [Lillooett] B.C., unceded territory to this day.](https://education.afn.ca/afntoolkit/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/book_4_1_1_siwashes-1024x768.jpg)

The last of the historical treaties were signed in 1923. Government policy moved increasingly towards enfranchisement and laws that would prohibit First Nations sovereignty, including making it a criminal offence for a First Nation to hire a lawyer to pursue land claims settlements.

Consequently, treaties were never concluded with First Nations in some parts of Canada, including most of British Columbia. First Nations without treaties assert their rights to their lands as the land was not ceded to the government.

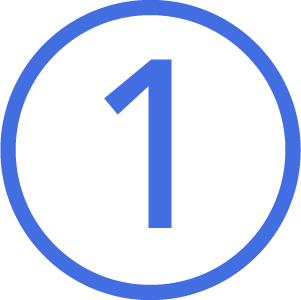

Modern Treaties in Canada: 1975-Present

Modern treaties are also known as comprehensive land claims agreements. A Standing Senate Committee on Aboriginal Peoples report states that “Treaties are solemn agreements that set out promises, obligations, and benefits for both the Aboriginal peoples and the Crown in right of Canada.”

View the signatures page from Nisga’a Final Agreement.

jpeg • 234 KB

Modern Treaties/Comprehensive Land Claims and Self Government Agreements

Modern Treaties/Comprehensive Land Claims and Self Government Agreements

Interpretations and Perspectives

The history, interpretation and implementation of treaties have been, and continue to be, contentious and controversial.

Critics have made some compelling arguments that all treaties are potentially flawed and subject to re-examination. This quote summarizes some of the complexities of dealing with the content and meaning of treaties and of resolving treaty disputes:

For an understanding of the relationship between the Treaty Peoples and the Crown of Great Britain and later Canada, one must consider a number of factors beyond the treaty’s written text. First, the written text expresses only the government of Canada’s view of the treaty relationship: it does not embody the negotiated agreement. Even the written versions of treaties have been subject to considerable interpretation, and they may be scantily supported by reports or other information about the treaty negotiations.

—Sharon H. Venne, “Understanding Treaty 6: An Indigenous Perspective” in M. Asch, ed., Aboriginal and Treaty Rights in Canada (2002)

The Canadians (British) and the First Nations were at the same meetings, listened to the same speeches (translated) and signed the same pieces of paper. Yet they had (and still have) two totally different concepts of what the treaties were about, and what each side was promising. The differences in understanding are rooted in two totally different worldviews, and two totally different concepts of land ownership and two colliding purposes.

![The image displayed here is the symbol of the Five-Nations Haudenosaunee [Iroquois] Confederacy, and is otherwise known as the Hiawatha Wampum.](https://education.afn.ca/afntoolkit/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/book_4_1_1_five_nations-scaled.jpg)

![Women and children [of Brunswick House First Nation] at the feast during Treaty 9 payment ceremony at [the Hudson’s Bay Company Post called] New Brunswick House, Ontario.](https://education.afn.ca/afntoolkit/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/book_4_1_1_treaty-brunswick.jpg)

![British Columbian Siwashes. Lilloett, [Lillooett] B.C., unceded territory to this day.](https://education.afn.ca/afntoolkit/wp-content/uploads/2021/04/book_4_1_1_siwashes.jpg)